About the third Science article

This is the third Science article published by the Nyiri group in five years. As a Science article goes, each one contains a breakthrough discovery about the structure and function of the brain. The first three authors of the current article are two PhD students and an undergraduate, and for the first author Krisztián Zichó PhD student, it is the second Science paper with his first authorship.

The story of Gábor Nyiri's group and their results is not the subject of this article, but there is no present without a past, so we have to step back a few years, at least until 2019. That's when two Science articles were published. In one of them, Krisztián Zichó, then sixth-year medical student had a shared first authorship. Today he is the first author of this third Science article of the group and still a PhD student.

But let's start the discussion with sixth-year medical student Réka Sebestény, who is the third author of this Science paper, but Gábor Nyiri, the group leader and corresponding author of the paper, thought that Réka should be given a chance to speak alongside second authors Krisztián and Boldizsár Balog, given that even the third author of such a paper has contributed fundamental discoveries.

- To be included in an article as a student, and in a prominent position as third author, is a great honour, and the fact that it's a Science article is something that not many people get. You certainly deserved it, because according to the others, you deserved it. The acceptance of an article depends on a lot of things . . .

- And a Science article certainly has even more! But we've made a breakthrough discovery, identifying a previously unknown brain nucleus and revealing its functional role in key processes such as reward, motivation and aversion. All this was achieved using an interdisciplinary approach and a robust methodology combining optogenetics, photometry, electrophysiology and behavioural experiments. Fortunately, this was also convincing for Science.

- When did you start working on this topic, what experiments did you do?

- I worked with Krisztián from the beginning of the project, when we discovered this new group of cells. I contributed to the anatomical and behavioural results of the project, performed several stereotaxic surgeries and assisted in almost all behavioural experiments.

- How important did you feel it was to work with Krisztián and the others?

- A job like this requires constant collaboration. Not only do we work together, but we are constantly discussing individual results and exchanging ideas for further experiments.

- Do you remember the moment when you felt that you had overcome the difficulties and that everything had fallen into place?

- Personally, I don't think you can be completely satisfied until your project is finally accepted by a journal. You are always, at every step, worried about what could go wrong. Obviously, there is a sense of satisfaction and joy when at the end of a long behavioural experiment the results confirm what you assumed, but the real relief comes only at the very end.

- What did you learn while writing this article, what was your challenge?

- For me, it was one of the first times I had witnessed and participated in the writing and compilation of an article, and one of such an exceptional calibre. I learned a lot from it. I gained insight into how to structure complex scientific results in a clear and effective way, how to work effectively with a multidisciplinary team, and how to manage feedback from reviewers. It was a challenging but highly rewarding experience that deepened my knowledge of scientific communication and taught me the importance of accuracy and clarity in the presentation of research results. My writing responsibilities were primarily in the preparation of the figure descriptions.

- You identified a group of brain nuclei and brain cells of clinical importance.

Do you think we can expect many more similar discoveries? What technical advances do you expect?

- Given the uninterrupted progress in neuroscience and imaging techniques, I think we can expect breakthrough discoveries in the coming years. And with the increasing precision of optogenetics, photometry and advanced molecular profiling, it may become somewhat easier to identify new brain structures and networks and, in particular, to study those of clinical relevance in more detail.

- What will happen with the techniques you are using now?

- They are likely to remain indispensable for a long time to come, providing deep insights into neuronal networks at both anatomical and functional levels. New technologies could of course make them even more efficient.

Boldizsár Balog is a PhD student, which also means he has been working in Gábor Nyiri's group for four years longer than Réka. And in a world where no one takes research lightly, that means a lot.

Asked what he thought it took to get Science to accept their manuscript, Boldizsár replied:

- First of all, it took finding the SVTg (subventricular tegmentum) cell population and realising its importance! It also took the last authors to pave the way for the experiments with seemingly endless grant writing and advice. Thanks also to our assistants - Emőke, Kati and Nándi - for all their help. We also needed good ideas and experience to select the most important and promising ones. It also needed the perseverance of all participants, which is nothing new, as all prestigious papers need them, as well as some luck to come up with good hypotheses and find the most exciting results in the mass of measurement data.

- Every scientific journal receives submissions of discoveries, new hypotheses, which of course vary greatly in importance. Meeting Science's notoriously high standards for a less significant discovery is a waste of time, money and energy. What do you think was the most rewarded and recognised?

- The initial idea for the work was already strong, and we used more and more new methods. These included retrograde tracing, fibre photometry, in vivo and in vitro electrophysiology, single-cell RNA sequencing. And by combining these methods, we were able to investigate questions that had not been possible before. Fortunately, our measurements yielded surprising results and our hypotheses were good!

- It's clear - although it wasn't easy to do! When did you start working on this project?

- My first work with the SVTg cell population was the activity measurement experiments I started in 2022. The most important of the results I measured is that SVTg cells are activated to both positive and negative stimuli.

- What could be the reason for this?

- It is thought that while we are experiencing good experiences, SVTg inhibits networks associated with bad experiences, ensuring that we can experience good experiences. Interestingly, SVTg is also activated during negative experiences, possibly protecting animals from escalating fear into panic.

- What was your role in this huge project?

- I spent most of my time designing and carrying out the experiments and evaluating and describing their results, but I also spent a lot of time designing and building new tools for the methods needed to do them, and checking their operation. It was a good experience. It taught me how I can make my work even more effective in the future. When you condense the results of a long series of experiments into a single diagram, you really learn what to look out for in the next similar experiment.

- In addition to your innovative methods, you have also decided to order the authors in a different way than is usually done in groups.

- The order of the authors was decided on the basis of the overall percentage of the results described in the article that each author contributed. We recorded everyone's contribution per task in a table, and the totals gave the author order. I like this approach!

- And what do you think about the joint work, the sharing of tasks?

- In our research, because of the labour-intensive nature of the experiments, it is not possible to produce surprising and relevant results alone, so it is important to collaborate. We brainstormed, experimented and discussed the results together.

- What was the "most exciting" experiment for you?

- Measuring brain activity. Meanwhile, I can see the mouse's brain activity in real time, so it's like reading its mind. When we saw from the signals that they were indeed related to SVTg activity, we were very pleased that the experiment had been well designed and the method had been used properly!

- You have found, identified - named - a clinically important brain nucleus/cell group, the SVTg (subventricular tegmentum). Réka is certainly not alone in her opinion that we can expect more similar discoveries. But how much of a role will microscopy play in this? It has been described by many as a method long past its prime...

- With newer and newer methods, we can map the brain in a level of detail that would not have been possible a few decades ago. In this respect, I think that today's neuroscience is a bit like the age of geographic exploration, with plenty more to discover. Microscopes will always be needed to identify tiny mouse brain areas, and new images will always need to be made, because, for example, combining retrograde trajectory tracking with microscopy, immunohistochemistry or even fibre photometry, there is plenty to discover. Of course, you can't write a big article today with just immunostaining and imaging.

It is clear that it took the important observations of Krisztián Zichó to bring this work to fruition with the collaboration of many. I wonder what we can learn from him?

- What do you think got the editors of Science interested?

- We found something really important and interesting. The previously unknown brainstem nucleus we described controls one of the most fundamental higher cognitive functions - reward.

- Indeed, the role of reward-punishment is fundamental, although its importance seems to have been taken less seriously than that of punishment.

Why has this area not yet been explored?

- It is indeed interesting, because by the end of the 20th century the brain was very well mapped at the level of regions, nuclei and pathways. I also think it is a rarity that we have only now managed to describe this brainstem nucleus, which has a significant number of cells and is also dominant in its function. I suppose that this contributed to the fact that our manuscript attracted the interest of the editors of Science and was finally well reviewed.

- Your colleagues also highlighted the diversity and novelty of the methods used!

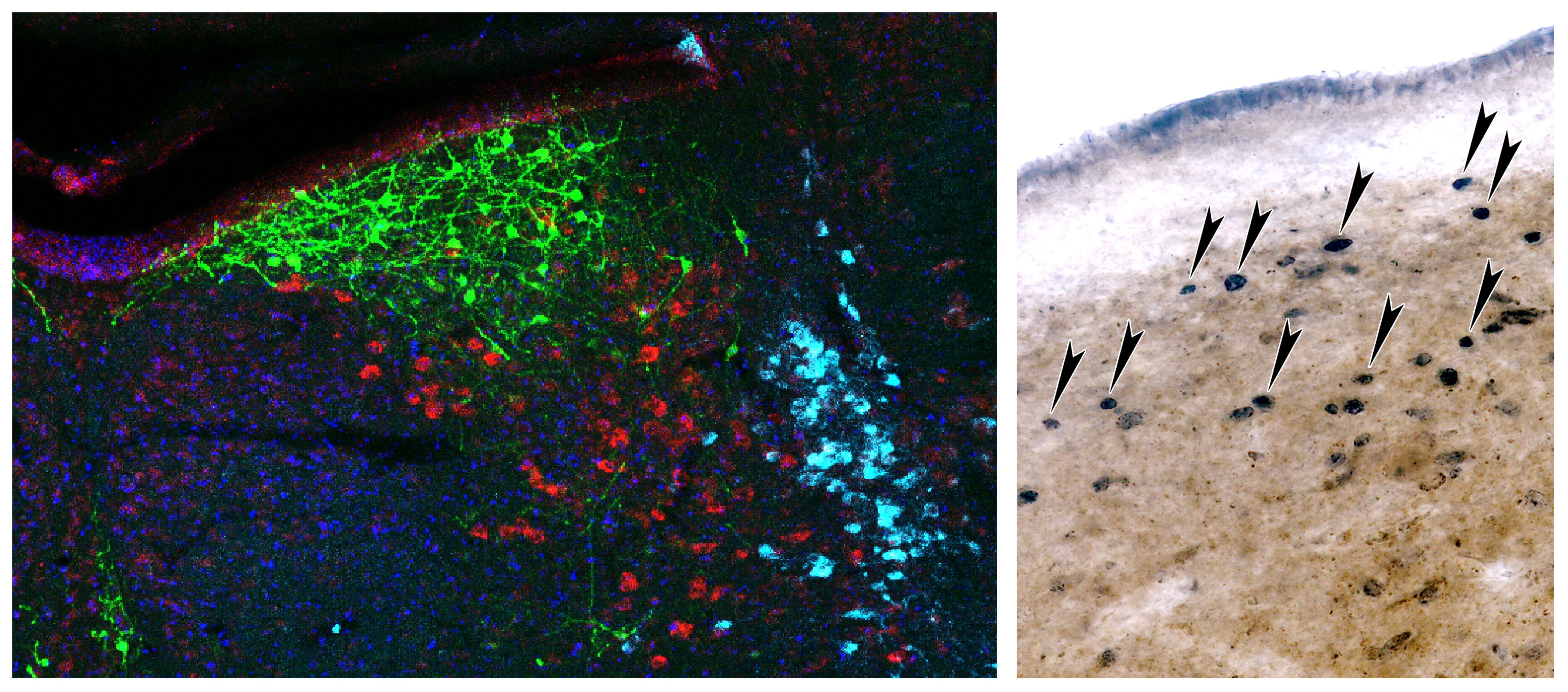

- This rare and interesting thing we found was described in the greatest possible detail, from an extremely diverse approach. We have used a wide range of methods, from combining anatomy and microscopy, to genetic and electrophysiological experiments, to fibre photometry and optogenetic behaviour experiments. The results resulted in a 120-page manuscript with 8 main and 21 supplementary figures and 12 large tables.

The sheer size and diversity of the work was enough to pique the interest of the editorial team!

- Only after you, of course, but my hat is off to the reviewers who have taken the trouble to review such an unusual methodology and such a huge article!

- It was not an easy task, that is for sure, but I would like to highlight those to whom I feel I owe a personal thank you!

Boldizsár, who, in addition to carrying out the photometric measurements and their analysis, developed a motion detection sensor to analyse the freezing of animals when they stiffen in response to an unexpected stimulus. Réka, who has done a lot of work performing surgery on hundreds of mice using viruses and/or optical fibres, has been instrumental in the execution and evaluation of anatomical and behavioural experiments.

We have János Brunner and János Szabadics to thank for the beautiful in vitro electrophysiological measurements that described the basic firing properties of these cells, and they collected for us the genetic material of the cells whose sequence was eventually determined by Charlotte in Csaba Földy's lab at the University of Zurich. The beautiful electron microscope images, measurements and cell reconstructions of Virág Takács have revealed further details about the anatomical relationships of these cells.

In vivo electrophysiological measurements by Albert Barth have shown how quickly and efficiently this pathway can inhibit lateral habenula (LHb). We are indebted to Áron Orosz for the execution of the c-Fos experiments and for a number of imaging works, and to Hunor Sebők for help with anatomical computational work.

Manó Aliczki and Éva Mikics deserve credit for finally realizing an optogenetic self-dosage experiment. In this way, we have shown that stimulation of these cells induces a similar self-administration as stimulation of dopaminergic cells, which are the reward centre. This result also demonstrates the importance and specificity of this nucleus.

We also owe a lot to our assistants (as pointed out by Boldizsár), who allowed the work to run more smoothly.

However, I owe the biggest thanks to Gábor, because he is the one who encouraged me that these cells would be worth investigating, and together we conceived and designed most of our experiments from start to finish.

- In an article, especially one that has been carried out with broad collaboration, an acknowledgement is not only appropriate but essential. And here, in this context, you have even revealed a lot about the methods used and, in some cases, the results.

The details of the methods you used would probably not be easy for most readers of our website to understand, but surely you can highlight something that helps them.

- In early 2022, we saw the SVTg brainstem nucleus, which has never been described and named by anyone before us. We did a lot of guesswork to figure out its function, and perhaps most surprisingly, we were able to elicit very strong behavioural responses from this nucleus by both stimulating and inhibiting it. I've been doing behavioural experiments for a long time, but you rarely see such strong effects, and when you do, you're always amazed. :)

The most difficult were probably the fiber photometry measurements. None of us had ever done such a measurement before, so the methodological challenge was considerable, and I tried to help Boldizsár with the solution.

The identification of these cells in humans did not go smoothly either, so I remember being delighted when I saw these stained SVTg cells on human sections under the microscope after the DAB call.

- Réka said she believes that one cannot be really happy until the results of a project are accepted. Can you agree with that?

- Basically, yes. This project was very complex, we expected an important result from each part of the project from the beginning until the submission of the manuscript. We were very happy with every single result that was done in different ways, because we knew that no one had seen it before us, but there was no point where we could sit back.

- Until almost 2019, when your first Science paper was published, Gábor's group was thought by many to be at the highest possible level of applying different microscopic methods, working hard and writing nice papers, but with the techniques they use, it is hard to make really big discoveries. Since then, this premature opinion has also been disproved!

- Microscopy has been a major contributor to our discoveries and has provided the basis for them, but our results and what we have to say are also based on a number of functional experiments. I think that function is worth exploring and understanding first, after which I think it is important to use classical anatomical microscopy methods to study the location of cells, their projection patterns, the relationships between cells and how they change. This is why I think microscopy will remain an indispensable method in system neuroscience for a long time to come.

- What next?

- We see that there are many undiscovered parts of the brainstem (nuclei, pathways, cell clusters) that not only have autonomic functions, but also have a significant impact on our mood, emotions, cognition, and thus may play a role in the development of many psychiatric diseases. Moreover, we believe that research in these areas could be really important if this work is published in Science.

The cells of the familiar laterodorsal tegmentum are marked in red, the cells of the locus coeruleus in turquoise.

On the right, SVTg neurons identified in the human brainstem are indicated by the black arrows in the brain section.