Untangling the "brain fog", or a breakthrough in understanding the brain's thyroid hormone homeostasis

The facts don't change what we think about them, but our lives are very much influenced by what is generally accepted in the treatment of, for example, a disease. Millions of lives and quality of life are affected if experimental results and observations show that we need to think differently, that we need a paradigm shift. This is what is happening now with thyroid hormone, with the active involvement of Balázs Gereben and his team.

Their discovery was published in the journal PNAS.

Richárd Sinkó, the first author of the paper, has so much to tell us about this that we'd better get straight to the point. To be sure, let's briefly summarise what we learned in high school: The thyroid gland produces and stores two important hormones. The tyrosine-based amino acid derivative thyroxine (T4) contains four iodine atoms and triiodothyronine (T3) contains three iodine atoms, and is released into the bloodstream by thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH). The amount of circulating T4 in humans is almost ten times that of T3, but it is T3 that is responsible for the hormone's action. We now also know, and this is no longer high school stuff, that T4 is converted toT3 in cells by the enzyme type 2 deiodase (D2).

- What else do we know?

SR:

- In recent decades, it has become known that thyroid hormone (PMH) homeostasis is regulated at multiple levels. A central neuroendocrine axis, the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid (HHP) axis, is responsible for regulating circulating PMH levels, but there is also a local regulatory system in tissues, which is different in each tissue. This allows each tissue to utilise circulating PMH in a unique way, making the hormone action tissue-specific.

- Unfortunately, this is not textbook for everyone. . .

- PMH household diseases affect hundreds of millions of people. The most common disorder is hypothyroidism, or systemic PMH deficiency. Untreated hypothyroidism, especially when severe, is a hellish condition. A long-term untreated patient will definitely need help to support themselves or to work. Those who go untreated for a long time will die sooner or later, so yes, they need to be treated. Hormone replacement can make a drastic difference to a patient's life in just a few days. In most cases, the improvement is real and spectacular.

- What does that mean today?

- Thyroxine monotherapy. This is by far the most common treatment at the moment. And the prevalence of the disease is such that thyroxine, prescribed as a hormone replacement, is often the most prescribed drug.

- I understand that animal hormone preparations were also the first to be used for thyroid hormone-related diseases. Can you tell us a little bit about this and the road to the introduction of T4 monotherapy?

- It used to be that all hypothyroidism was treated with animal thyroid supplements and other preparations, which was not as easy as it sounds. It didn't matter what animal the product came from, and because of the fluctuating quality, it was more difficult to administer.

The road to thyroxine monotherapy dates back to the first third of the 20th century. Although the structure of thyroxine was already known by the 1930s, its industrial production was not achieved until decades later. For a long time, it was not even known that T3 existed alongside T4, and that T3 could be produced from T4 in the periphery was not discovered until 1970. It was a paradigm shift - a change of mindset about something based on new scientific findings - that has been the fundamental approach to the treatment of hypothyroidism to this day.

- What became the new paradigm?

- We put the body in charge of the effectiveness of the therapy! Give the patient the prohormone T4, which is cheaper, its dose is easier to adjust, and the body will then adapt and adjust to the optimal hormonal conditions for it. The efficacy of the intervention is monitored/checked by determining circulating TSH and PMH, but especially TSH, which also became a routine diagnostic method in the 1970s.

- How effective is this T4 monotherapy?

- Since the 1970s it has produced excellent results and a real improvement in the quality of life for the vast majority of patients. However, an increasing number of results have recently shown that around 15% of patients treated with this treatment still have sometimes severe, predominantly neurological symptoms. These include brain fog, but can also include depression and suicidal thoughts. And all this is true for millions of patients, despite the fact that their circulating TSH levels have been normalised by therapy! So on paper you are cured!

- Before I ask you any more questions about this 15%, let me first find out what is a "brain fog"?

- A brain fog is a combination of several cognitive and mental disorders, symptoms. It includes memory disturbances, mood swings, lethargy, fatigue, when you find it harder to find words, slower to understand things. It's really like having your thoughts in a fog.

- So are there 15% left that we can't help? That is a lot, even if the 85% is almost six times as much. At least to some extent, but does treatment help that 15%?

- Those who respond worse to T4 monotherapy also have differences. For some it does some good, but they still don't feel great (or rather mind numbing), while others experience virtually no change.

Another major difficulty in assessing the lasting symptoms is that the symptoms of hypothyroidism are not very specific. It is difficult to tell whether someone is depressed because they are depressed or because they need to adjust their T4 dose a little more. And why would you even think of adjusting your T4 dose once your TSH is normal, so there's nothing wrong with you?

- What could be the reason for the discrepancy between the 15% of patients?

- Some of the reasons are already known. For example, one of the causes is a polymorphism in the D2 enzyme, which is common and only causes real problems if the person carries it as a homozygote. In this case, the D2 enzyme is located in the membrane of the Golgi apparatus rather than in the endoplasmic reticulum. Although the translocated D2 is still able to produce T3, the translocation induces a strong stress in the cell, which can only be compensated for with great effort. This would be fine, but if the patient needs T4 therapy, the defective D2 can no longer cope with the combination of cell stress and elevated T4 and makes poor use of T4. Such patients make up a significant proportion of the 15% and for them some additional therapy would be particularly important.

- Is there such an option?

- Few complementary therapies are available at present. The most common view among advocates of change is the wider use of T4+T3 combination therapy, but this is not available in all countries. At present, it is also difficult to know whether a patient is really in the 15%, and the burden of treatment is higher for the patient.

- The reason and timeliness of your research needs no further explanation, but rather how!

- First, we wanted to know how the ingested T4 is utilized in the nervous system and what are the region-specific characteristics of the PMH effect in the presence of excess T4. To do this, we used our patented THAI (Thyroid Hormone Action Indicator) mouse, which allows us to specifically determine the PMH household of the brain regions under study. Using the THAI model, it was demonstrated that different brain regions respond differently to the same T4 treatment. While in some regions the same amount of T4 could normalize the PMH effect, in other regions it was insufficient or even excessive. Different brain regions would therefore need different T4 doses to restore the local PMH household.

- What could be the reason for this?

- It is known that although D2 converts T4 to T3, T4 can inactivate D2. The more T4 there is, the less efficiently the enzyme can produce T3 because it is inactivated during conversion. All of this suggested that D2 was the cause of the differences.

The D2 enzyme is under complex regulation. It is not only inactivated by T4 but also degraded by a mechanism called ubiquitination. This greatly attenuates T3 production in the tissue. However, the cell can protect D2 from degradation. This is achieved by the opposite process of ubiquitination, deubiquitination. The two processes can be very sensitively regulated by the cell. Tissue T3 production thus depends on a delicate balance of D2 degradation and regeneration.

- How does this explain the differences in T4 use between brain areas?

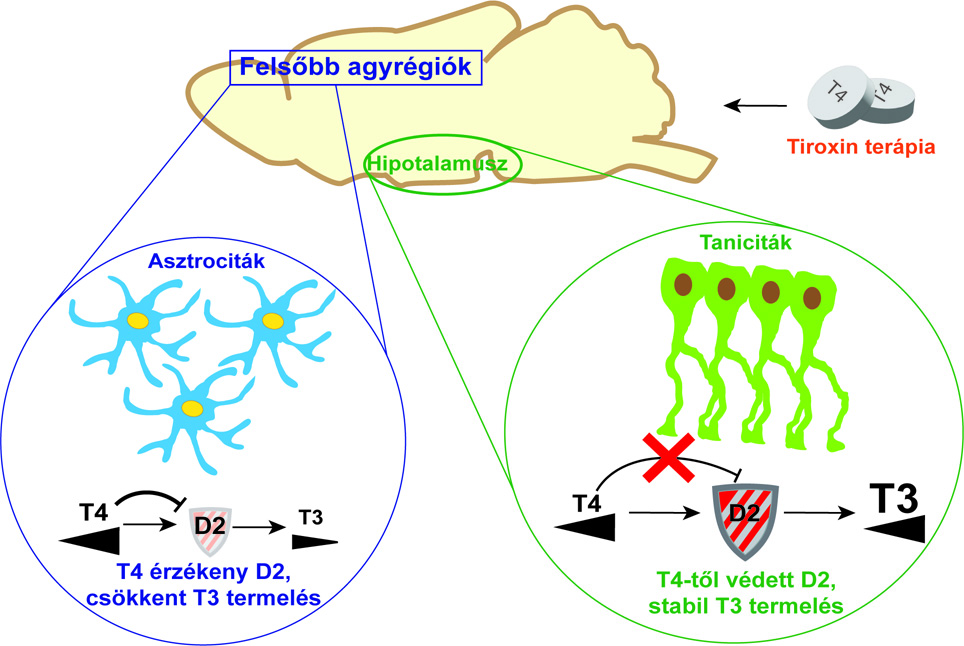

- It is important to stress that only a few cell types in the brain produce D2. These are specifically glial cells, usually astrocytes. It was therefore useful to investigate the D2 regulation of astrocytes.

However, in the hypothalamus, a specific type of glial cell, tanicytes, produce D2. Tanicytes are thus essential players in the regulation of central neuroendocrine axis (HHP) function, as mentioned above, and thus of circulating PMH levels. Taking these into account, we suspected that the region-specific features observed in T4 utilization are due to differential D2 regulation by tanicytes and astrocytes.

- And what did you find?

- The creation of the cell cultures themselves was not easy, but Petra Mohácsik, Emese Halmos and Andrea Juhász did not give up. Using the cell cultures, we showed that one of the main reasons for the difference between cortical and hypothalamic D2 regulation is different deubiquitination, i.e. the protection of the D2 enzyme. While the strategy of tanicytes is to preserve enzyme stores by increased deubiquitination, cortical astrocytes sacrifice D2 in the presence of T4 excess.

- This different regulation is innate in us, so there is an important reason for it. What do you think?

- Tissues need T3 at different places, times and amounts, which is well managed through fine-tuning the breakdown and regeneration of D2. Inactivation of D2 by T4 plays a key role in this. In the higher brain regions outside the hypothalamus, the process aims at maintaining the stability of the tissue PMH household. The surplus of thyroxine introduced by treatment in these regions is overdone and has the opposite effect. The more thyroxine, the less T3 production.

However, the T4 sensitivity of the D2 enzyme is more complex with respect to the HHP axis responsible for regulating circulating PMH levels. Normally, circulating hormone levels are stabilised in a self-regulating manner by negative feedback. That is, when hormone levels rise, axis function is reduced, and vice versa.

- How is the hypothalamus able to sense and regulate circulating hormone levels if the essential D2 - functions with variable efficiency?

- Using the THAI mouse, we have shown that hypothalamic D2 activity is resistant to changes in T4 levels. Because of this, hypothalamic T3 production can sensitively track changes in circulating PMH levels to see what is happening in the body. This is why feedback regulation of the HHP axis can work. This mechanism also works with ingested excess T4 and normalises TSH, but outside the hypothalamus this no longer represents normal functioning of the PMH household.

- What is the significance of this for T4 therapy?

- Due to the iodine-deficient environment affecting the masses during phylogeny, the mammalian organism has developed adaptations to overcome reduced PMH levels, but increased T4 intake does not occur naturally and our bodies do not have an effective enough response. The mechanism we have identified has revealed the molecular reasons for this.

Thyroid hormone is activated with different efficacy in different brain regions due to cell type-specific regulation of the D2 enzyme. This may result in a hormone deficiency in higher brain areas under the influence of excess T4, despite normal thyroid hormone action in the hypothalamus, the centre of hormone metabolism. As a consequence, blood parameters used for routine characterisation of thyroid hormone balance are normalised.

The work was carried out in collaboration with AC Bianco's group at the University of Chicago and the Integrative Neuroendocrinology Research Group led by Csaba Fekete. The research was supported by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the National Laboratory for Translational Neuroscience (NKFIH). The study was first authored by Richárd Sinkó and published in the journal PNAS.