COVID and microglia

The latest article from Ádám Dénes' group was published in Nature Neuroscience, the leading journal in neuroscience research. This should be a cause for celebration, as it is no mean feat to publish in this journal, and why shouldn't the team be happy that their paper has received a lot of press coverage. But the point is not only more than that, it is much more important: their findings may in the future offer the possibility of improving the quality of life of people living with long-COVID syndrome and, what is more, of better understanding neurodegenerative diseases.

The recent pandemic, which has claimed millions of lives, has left a world changed in many ways. It is both unfortunate and dangerous that few have not forgotten the lessons of the epidemic, because the majority of people would be vulnerable to a similar challenge again. Fortunately, there are those who have not forgotten what happened and are still doing their bit to ensure that we are not left unprotected in the face of similar situations. We talked to the first author of the Nature Neuroscience article, Rebeka Fekete, postdoctoral researcher and member of the group of Ádám Dénes, who led the research, about such research and its results.

- It is not at all uncommon for a paper accepted for publication in Nature to summarise the results of 7-10 years of research. But the start date of your work is not much to ask, as it can't be before 2020!

- It was exactly then, in 2020, that we started our COVID project and our lab was among the first in the world to receive official approval to perform autopsies on patients who died in COVID19.

- This was a bold and certainly an honourable undertaking. For a year, there was no vaccine, and the number of deaths in some places increased almost exponentially!

- Only one neuropathologist in the country, Tibor Hortobágyi, took the risk to perform the autopsies, manually, with the protective equipment available at the time - and yes, even vaccines were not available at the beginning.

And as the epidemic grew, we also faced the challenge that restrictions made logistics increasingly difficult.

- What are you referring to?

- The collection of samples was a very difficult process, and we had a lot of help from the pathology department of the National Institute of Pulmonology. The task required a great deal of flexibility, if only because the timing of the autopsies could not be planned in advance. Sometimes I received a call at 3 a.m. that new samples were arriving and we had to be ready to receive them immediately.

- People involved in epidemiological research understand particularly well why sample collection was essential, and what it means to be in a similar situation, literally in life-threatening circumstances, day in, day out, for many months. But how and why did your group, which has gained international fame for its findings on the brain's immune cell, microglia, start these Covid studies?

- As the epidemic spread, there were more and more reports of increased incidence of neurological problems, such as stroke, in patients who survived COVID19. So we've been monitoring the latest research on a daily basis to understand what changes are taking place in the brain and what correlations have been found in other labs.

- As a result, were you able to formulate a question you wanted to answer?

- Our research was not built around a single, pre-defined question, but rather a process that was constantly evolving. Initially, the basic questions - such as how COVID19 affects the nervous system - provided the basis for the project, but as we progressed, new challenges and interesting results emerged, each suggesting a new direction.

- What did you investigate first?

- The inflammatory and neuropathological changes in brain structures affected by COVID19. As more and more data was collected and analysed, the most important questions at the time were formulated.

We soon became certain of one thing. As we were receiving more and more frequent feedback from clinicians about brain inflammation, it seemed clear that microglia were likely to be involved in the development of complications of viral infection.

This is where we started our research.

- Given your achievements so far, you've had something to build on!

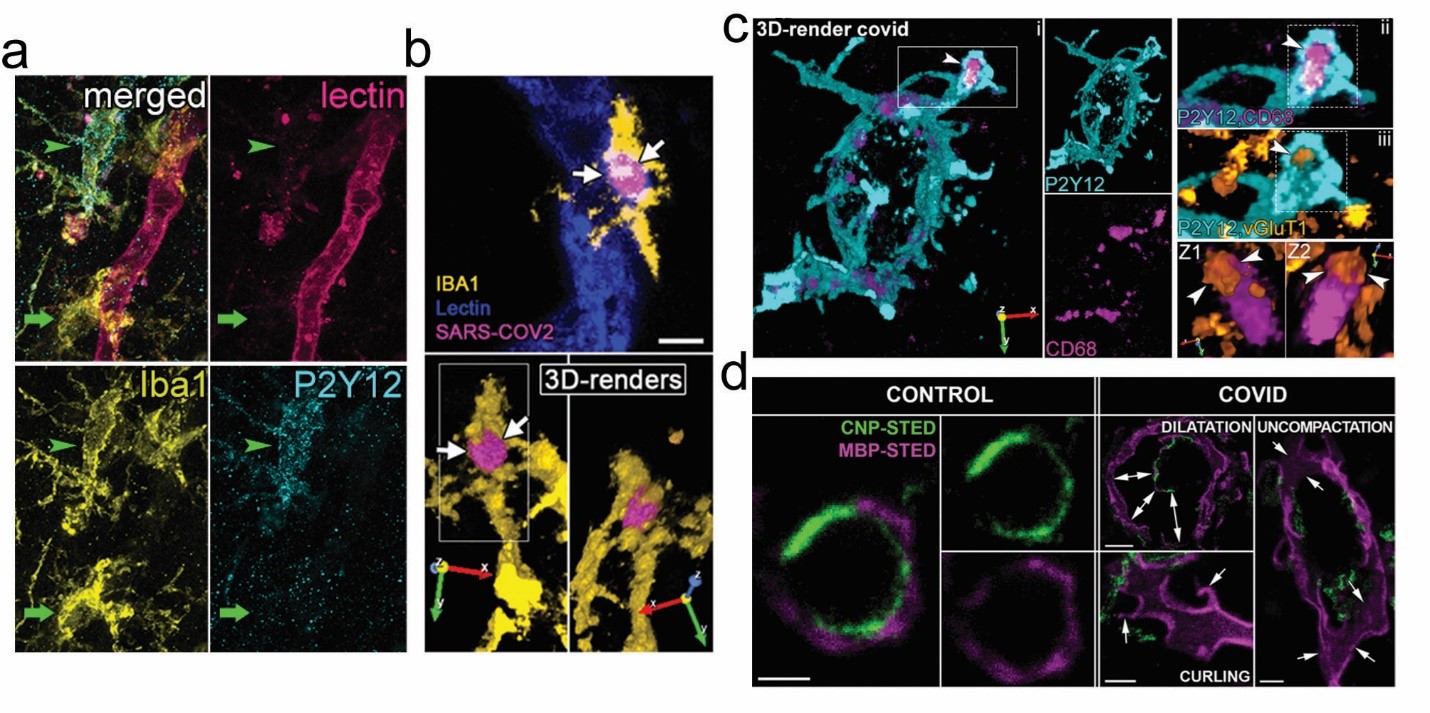

- Our previous work set the tone, there was really no question what to look at first. So we set out to investigate morphological changes in microglia, and then to investigate changes in microglial P2Y12 receptor levels. The basic information to be collected at the outset included finding the brain areas most affected.

By this time it was known that the virus mainly causes respiratory and circulatory problems, so these brain areas were prioritised.

- What kind of tests did you collect tissue samples for?

- Even before sample collection, it was important to have not only histological/anatomical results, but also to shed light on protein and RNA level mechanisms. We designed our sample collection protocol with this in mind. This was a pioneering method, which deviated substantially from the usual pathological protocol, but it allowed us to obtain results from our anatomically and functionally comparable mirror blocks by several methods in parallel. Thus, we were able to initiate the determination of different inflammatory factors and SARS-CoV-2 virus RNA from the mirror blocks in parallel with our histological investigations.

- A great idea, my sincere congratulations!

- The detection of the virus was also an important initial step. The results of the publications known until then did not contain any data that provided any histological validation, we did not know what a validated stain for virus looked like. The literature only provided us with qPCR test results, which did not even allow us to know for sure in which cell type the virus was hiding in the brain. After several antibody tests and protocol refinements, we found the one antibody that allowed us to confidently label the nucleocapsid protein of SARS-CoV-2. Once we had validated/confirmed this result in lung tissue, we could only start looking in the brain.

- What was your involvement in these crucial experiments to get started and what do you consider your greatest contribution to the results?

- My involvement in the research did not start with the protocol design, as I was involved throughout the sample collection. I also regularly collected blood plasma samples from patients at Korányi Hospital. During the first two years, I processed all the tissue blocks, which included administration, embedding, incision, staining, microscopy and histological analysis.

- Not only did you not feel unemployed then, but you could not say that any day was boring or without danger!

- What's more, I had to learn, as samples were tested using a variety of methods requiring specialised knowledge! For this I received a lot of professional help and support from Csaba Cserép, Eszter Szabadits and Anette Schwarz, who are experts in electron microscopy, electron tomography and STED microscopy methods in our group.

- Besides???

- I also had the task of carefully examining the laboratory data and pathology reports of the COVID19 cases to see if there was any correlation between the brain inflammation and the clinical laboratory data.

- This could not be an easy task either, especially as the medical background of the deceased prior to COVID19 was varied.

- At the same time, I started processing frozen samples for molecular biology assays, which formed the basis for flow cytometry and qPCR analyses.

- Alone????

- I was assisted by Krisztina Tóth in the processing and measurement of the large number of tissue and blood samples. And within our institute, special thanks to László Acsády and Csaba Dávid for clarifying specific issues concerning the thalamic brain area.

- Speaking of acknowledgements, who from other institutes participated in the work?

- Szilvi Benkő and Eduárd Bíró (University of Debrecen) were instrumental in this work, not only by performing the technical qPCR measurements, but also by identifying the pattern recognition receptors underlying the inflammatory processes.

We also thank Attila Csikász-Nagy, Erzsébet Fichó and János Szalma for the application of artificial intelligence, which contributed to the success of the research. And Arthur Liesz and Alba Simats (Institute for Stroke and Dementia Research, Munich) were the international collaboration partners of the project.

- To organise such a large piece of work well requires a special talent - in my opinion. What was your experience?

- The biggest challenge for me was that I got involved in a complex human study relatively suddenly, where I needed a completely different approach and working methods than I had used in mouse-based research, where if a measurement failed, we had the possibility to include additional animals. Here, each block of tissue was unique and unrepeatable, we were working with enormous responsibility, which was also a professional challenge, and we had to communicate with clinicians all the time. But our tissue bank is unique and we can use it to answer many more research questions.

- This tissue bank itself is a huge achievement!

- Our COVID19 tissue bank is unique in itself because while it relies on a large number of elements in clinical research, similar levels of processing are rarely available. This compensates for the fact that we could not have samples in the hundreds, which is not a problem for blood samples, for example.

It was surprising that, despite the small number of elements, we found strong associations between brain inflammation and peripheral inflammatory processes in the only 13 COVID19 cases available to us.

- Were there any difficulties worth mentioning in obtaining the samples?

- We had to collect control samples alongside the COVID19 cases, of course, and this was extremely slow during the epidemic. Because of this, we had to use alternative sources. The HAL (Human Brain Laboratory) group led by Zsófia Maglóczky, the brain bank of Professor Miklós Palkovits and a Dutch brain bank were very helpful in this. We compared these with the samples of the COVID cases and were able to describe the observed changes.

- What did you find most difficult about writing the Nature Neuroscience article?

- It was a requirement to present the results accurately and in depth, but also to provide a clear and understandable summary for the scientific community. In addition, we had to meet strict methodological and statistical requirements, as well as credibly convey the complexity of the research.

- As I saw the multitude of experiments, methods and data, the complexity of the transfer was the least of your problems... But seriously, you were not alone in writing it!

- Far from it! This project would not have been possible without Ádám Dénes, who managed the whole research process and took the lion's share in writing the article. I'm also very grateful to Csaba Cserép and Balázs Pósfai, who provided tremendous professional help in data processing, editing the figures and writing the article. Their thoroughness and dedication played a key role in the high quality of the final result. Thank you very much for your work together!

- Finally, for non-experts, please summarise in one sentence what you think is the main achievement and significance of this great and great work!

- In the course of our work, we have mapped out mechanisms that, in addition to providing an opportunity to improve the quality of life of people living with long-COVID syndrome in the future, will also lead to a better understanding of other neurodegenerative diseases.